Theme 1/

Diet and Ecology

Summary/Findings

One of GSN’s most important sites is Zaraa Uul, or Hedgehog Mountain (DE, Fig. 1 – Zaraa Uul) (Odsuren et al. 2015). 35,000 to 30,000 years ago (during the Early Upper Palaeolithic), much of this grassland was a massive saline (salty) lake. It dried out during the Last Glacial Maximum (~25,000-18,000 years ago) and then by 8500 years ago (during the Neolithic) it was filled with freshwater marshes. Today, it is a rich grassland where local herders graze their cows, horses, sheep and goats.

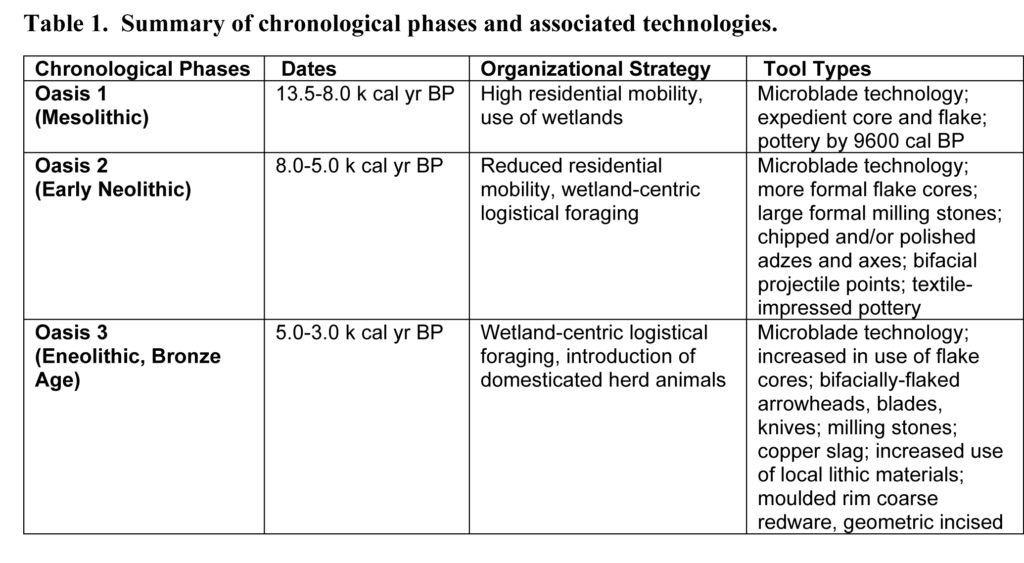

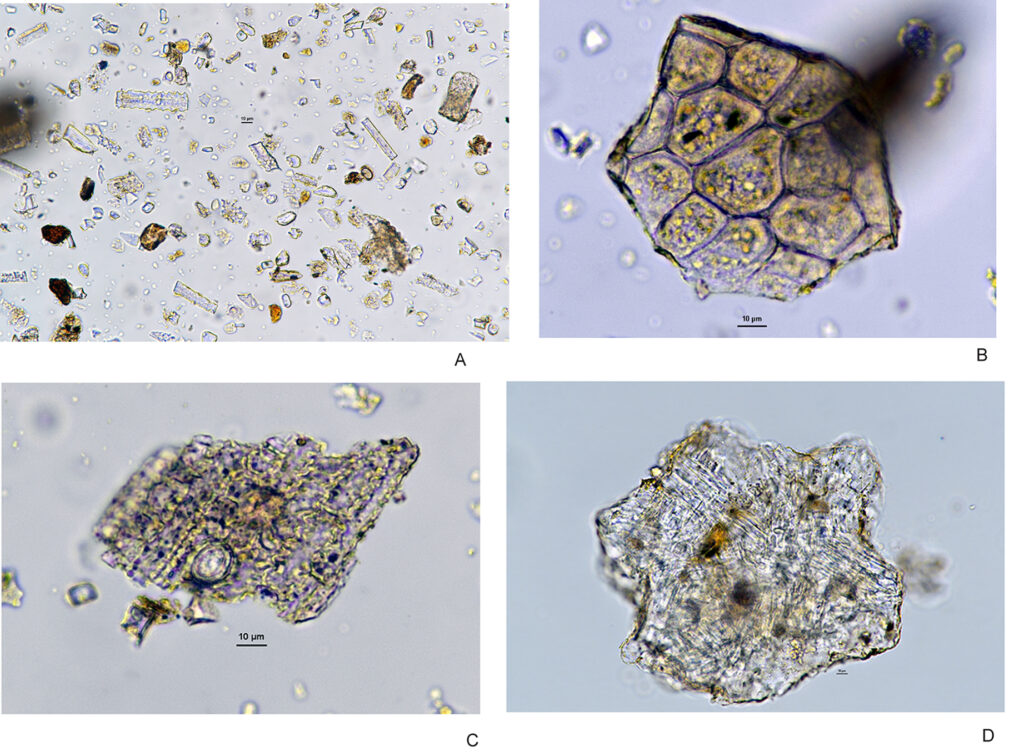

When we started working at this site it was to study the stone tools and animal bones left behind by hunter-gatherers between 8500 and 3000 years ago (Janz 2012). Early researchers knew that the local “Neolithic” period was important because the archaeological sites from this time period were really different: instead of roaming widely across the region with only small campsites they settled around shallow lakes and marshes, especially those near dune-fields (DE, Fig 2 – Dune Site), and they began using new technologies like pottery (DE, Fig 3 – Pottery) and milling stones (, DE Fig 4 – Milling Stone) to more intensively process foods like seeds and other plants (Janz, Bukhchuluun and Odsuren 2017).

In 2007, we dated pottery from these sites and found that the Neolithic happened during the Holocene Climatic Optimum, a period when the environment was very wet and warm (Janz 2012; Janz, Feathers, and Burr 2015). This told us that the change in land-use and the introduction of new technologies were tightly connected with these environmental changes (Janz 2016). The warmer, wetter environment created neat little pockets (oases) where there were lots of plants and animals, making it possible for people to hunt and gather in one place for longer.

Why is this a new idea? Well, there is large body of scientific research about birds and other animals showing that in nature when animals look for food, they try to eat things that are going to give them the most calories for the least amount of work – we call this “optimal foraging.” Archaeologists have applied this to humans, suggesting that if humans are going to hunt something, they would rather hunt a big animal (with lots of meat and fat) than a small animal that is hard to catch. We think this way because many early human and pre-human archaeological sites have lots of evidence of people hunting large animals like wild cows, horses, and deer, but rarely have bones from small animals like birds, fish, or rabbits. The prevailing idea was that people only started hunting small animals because there were not enough big ones around – mostly because human population size increased over time and caused a strain on resources, but also because there were fewer large animals like mammoth and rhinoceros when they went extinct at the end of the Ice Age (Pleistocene).

As we develop better methods for understanding the past, new ideas have emerged: 1) people often do not hunt really huge animals like elephants and camels because it is both a lot of work and produces way too much meat (so maybe there is something really interesting happening when we do hunt these animals); 2) since people usually live together in groups, one of the important things about humans is that they divide different tasks among group members – some people might hunt deer while other people gather plants, or make baskets; and 3) people in the very ancient past, including Neanderthals, did not only hunt big game – they also sometimes gathered plants, fished, and hunted rabbits.

The animal bones from Otson Tsokhio, several hundred meters away from Zaraa Uul, shows that about 35,000 to 25,000 years ago, during the “Upper Palaeolithic” period, local people lived on the edge of a saltwater lake and were hunting large wild animals such as horses (DE, Fig. 5 – Horse Bones), mountain sheep, giant elk, and possibly even woolly rhinoceros (Janz et al. 2021). Some animals were probably very important to humans for reasons other than just food. In 2018, while excavating at Otson Tsokhio, we found a place where these early people had carefully sandwiched a young hyena skull between a giant elk leg bone and a rhino scapula (DE, Fig. 6 – Sandwich). Stone tools, animal bones, an ostrich eggshell bead, and red paintstone (ochre) were also found here.

After about 25,000 years ago, there was a period called the Last Glacial Maximum, when the environment was very dry and extremely cold. The lake dried out and people moved. By around 15,000 years ago, the environment had improved and small numbers of people lived across the Gobi Desert again. But it is only after 8500 years ago, when rainfall increased and the lake basins filled with freshwater marshes and lakes that the Gobi Desert became a great place to live again and people hunted a wider diversity of animals (DE, Fig. 7 – Histogram) and probably spent more time processing plant foods like grass seeds and tubers.

Zaraa Uul is one of the only Gobi Desert sites so far where we have animal bones to tell us what kind of animals people were hunting. We have found bones of wild horses and wild cattle, but also new evidence of animals people rarely hunted here during the Upper Palaeolithic – small deer, hare (DE, Fig. 8 – Hare Elements), fox, and even pheasant (Janz et al. 2021). Across the Gobi Desert, people were also putting a lot of work into cutting and polishing large stone to use for grinding plant foods like seeds and roots/bulbs (Dubreuil, Evoy, Janz 2021) or for working wood (DE, Fig. 9 – Adze) (Evoy 2019). People at Zaraa Uul also made small pestles (DE, Fig. 10 – Pestle) – perhaps for things like grinding herbs for medicine or minerals for paint pigments – and they made beads from freshwater mussel shells (DE, Fig. 11 – Shell Beads). Both of these periods of habitation – the Neolithic and Palaeolithic – took place under warmer and wetter conditions. But it takes a lot of work to shape stone tools, and to create and use pottery. Why all the extra work when the climate was good and resources were abundant?

There are some different explanations that we are thinking about. One is that major climate changes between periods made the environment so different that really large animals like giant elk and rhinoceros went extinct, and that the loss of these big animals made people have to find new foods to eat. Another is that new people with new food traditions moved into the area and that they had a different way of working together as a group, as well as different types of foods that they liked to eat. Another idea is that these new environments – with the close juxtaposition of forests, marshes, and steppe – offered such a variety of foods in one place, that people enjoyed being able to stay in one place and that they were healthier and happier when they had a richer and more diverse diet. As with most things, it is likely that a number of factors contributed and that all three of these factors worked together to change the way humans lived on the gobi-steppe.

Publications:

- 2024 Janz, L. Hunting, Herding, and Diet Breadth. A Landscape Based Approach to Niche Shifting in Subsistence Economies (Gobi Desert). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 76: 101624.

- 2021 Zhao, C., L. Janz, D. Bukhchuluun, and D. Odsuren. Neolithic pathways in East Asia: early sedentism on the Mongolian Plateau. Antiquity. DOI 10.15184/aqy.2020.236

- 2021 Dubreuil, L., A. Evoy, L. Janz. The New Oasis: Potential of Use-Wear for Studying Plant Exploitation in the Gobi Desert Neolithic. Access Archaeology (Archaeopress). (in press)

- 2019 ArchaeoGLOBE Project. Archaeological assessment reveals Earth’s early transformation through land use. Science. August 30, 2019. DOI 10.1126/science.aax1192

- 2017 Janz, L, D. Odsuren, D. Bukchuluun. Transitions in palaeoecology and technology, hunter-gatherers and early herders in the Gobi Desert. Journal of World Prehistory 30(1): 1-81. (in English with Mongolian abstract) DOI 10.1007/s10963-016-9100-5

- 2016 Janz, L. Fragmented landscapes and economies of abundance: the Broad Spectrum Revolution in arid East Asia. With comments and response. Current Anthropology 57(5): 537-564. DOI 10.10086/688436

- 2015 Odsuren, D., D. Bukchuluun, L. Janz. Preliminary results of Neolithic research conducted in eastern Mongolia. Studia Archaeologica 35: 72-96. (in Mongolian with English abstract)

- 2015 Janz, L., J. Feathers, and G. S. Burr. Dating surface assemblages using pottery and eggshell: assessing radiocarbon and luminescence techniques in Northeast Asia. Journal of Archaeological Science 57: 119-129. DOI 10.1016/j.jas.2015.02.006

- 2012 Chronology of Post-Glacial Settlement in the Gobi Desert and the Neolithization of Arid Mongolia and China. PhD Thesis. School of Anthropology, University of Arizona.